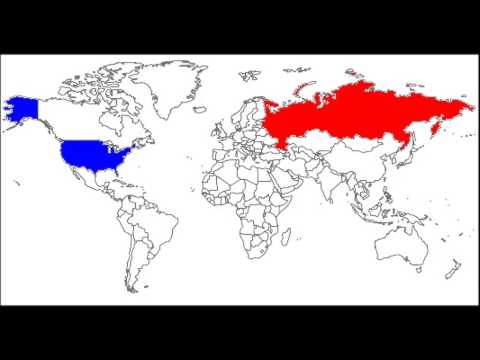

World War 3 Scenario

Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War - Kindle edition by Chossudovsky, Michel. Download it once and read it on your Kindle device, PC, phones or tablets. Use features like bookmarks, note taking and highlighting while reading Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War. Feb 03, 2019 Today I will present one of my scenarios. It is almost 100% original, and here I demonstrate what a third world war would be like in 2080. In this scenario, the United Kingdom and Germany collapsed, and the monarchy was implemented.

For the past 50 years, American leaders have been supremely confident that they could suffer military setbacks in places like Cuba or Vietnam without having their system of global hegemony, backed by the world’s wealthiest economy and finest military, affected. The country was, after all, the planet’s “indispensable nation,” as Secretary of State Madeleine Albright in 1998 (and other presidents and politicians have insisted ever since). The United States enjoyed a greater “disparity of power” over its would-be rivals than any empire ever, Yale historian Paul Kennedy in 2002. Certainly, it would remain “the sole superpower for decades to come,” Foreign Affairs magazine us just last year. During the 2016 campaign, candidate Donald Trump his supporters that “we’re gonna win with military.

We are gonna win so much you may even get tired of winning.” In August, while announcing his decision to send more troops to Afghanistan, Trump the nation: “In every generation, we have faced down evil, and we have always prevailed.” In this fast-changing world, only one thing was certain: When it really counted, the United States could never lose.No longer. The Trump White House may still be basking in the glow of America’s global supremacy but, just across the Potomac, the Pentagon has formed a more realistic view of its fading military superiority.

China’s ChallengeIndeed, military tensions between the two countries have been rising in the western Pacific since the summer of 2010. Just as Washington once used its wartime alliance with Great Britain to appropriate much of that fading empire’s global power after World War II, so Beijing began using profits from its export trade with the United States to fund a military challenge to its dominion over the waterways of Asia and the Pacific.Some telltale numbers suggest the nature of the future great power competition between Washington and Beijing that could determine the course of the 21st century. In April 2015, for instance, the Department of Agriculture that the US economy would grow by nearly 50 percent over the next 15 years, while China’s would expand by 300 percent, equaling or surpassing America’s around 2030.Similarly, in the critical race for worldwide patents, American leadership in technological innovation is clearly on the wane. In 2008, the United States still held the number two spot behind Japan in patent applications with 232,000. China was, however, in fast at 195,000, thanks to a blistering 400 percent increase since 2000.

By 2014, China actually took the in this critical category with 801,000 patents, nearly half the world’s total, compared to just 285,000 for the Americans. Current Issue. With supercomputing now critical for everything from code breaking to consumer products, China’s Defense Ministry the Pentagon for the first time in 2010, launching the world’s fastest supercomputer, the Tianhe-1A. For the next six years, Beijing produced the fastest machine and last year finally in a way that couldn’t be more crucial: with a supercomputer that had microprocessor chips made in China.

By then, it also had the most supercomputers with 167 compared to 165 for the United States and only 29 for Japan.Over the longer term, the American education system, that critical source of future scientists and innovators, has been falling behind its competitors. In 2012, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development tested half a million 15-year-olds worldwide. Those in Shanghai in math and science, while those in Massachusetts, “a strong-performing US state,” placed 20th in science and 27th in math. By 2015, America’s standing had to 25th in science and 39th in math.But why, you might ask, should anybody care about a bunch of 15-year-olds with backpacks, braces, and attitude? Because by 2030, they will be the mid-career scientists and engineers determining whose computers survive a cyber attack, whose satellites evade a missile strike, and whose economy has the next best thing.Rival Superpower StrategiesWith its growing resources, Beijing has been laying claim to an arc of islands and waters from Korea to Indonesia long dominated by the US Navy. In August 2010, after Washington expressed a “national interest” in the South China Sea and conducted naval exercises there to reinforce the claim, Beijing’s Global Times angrily that “the US-China wrestling match over the South China Sea issue has raised the stakes in deciding who the real future ruler of the planet will be.”Four years later, Beijing escalated its territorial claims to these waters, a nuclear submarine facility on Hainan Island and its dredging of seven artificial atolls for military bases in the Spratly Islands. When the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, in 2016, that these atolls gave China no territorial claim to the surrounding seas, Beijing’s Foreign Ministry the decision out of hand.

To meet China’s challenge on the high seas, the Pentagon began a succession of carrier groups on “freedom of navigation” cruises into the South China Sea. It also started shifting spare air and sea assets to a string of bases from Japan to Australia in a bid to strengthen its strategic position along the Asian littoral. Since the end of World War II, Washington has attempted to control the strategic Eurasian landmass from a network of NATO military bases in Europe and a chain of island bastions in the Pacific. China’s army has by now developed a sophisticated cyberwarfare through its Unit 61398 and allied contractors that “increasingly focuson companies involved in the critical infrastructure of the United States—its electrical power grid, gas lines, and waterworks.” After identifying that unit as responsible for a series of intellectual property thefts, Washington took the unprecedented step, in 2013, of filing criminal charges against five active-duty Chinese cyber officers.China has already made major technological advances that could prove decisive in any future war with Washington. Instead of competing across the board, Beijing, like many late adopters of technology, has strategically chosen key areas to pursue, particularly orbital satellites, which are a fulcrum for the effective weaponization of space.

As early as 2012, China had already launched 14 satellites into “three kinds of orbits” with “more satellites in high orbits andbetter anti-shielding capabilities than other systems.” Four years later, Beijing that it was on track to “cover the whole globe with a constellation of 35 satellites by 2020,” becoming second only to the United States when it comes to operational satellite systems.Playing catch-up, China has recently achieved a bold breakthrough in secure communications. In August 2016, three years after the Pentagon abandoned its own attempt at full-scale satellite security, Beijing the world’s first quantum satellite that transmits photons, believed to be “invulnerable to hacking,” rather than relying on more easily compromised radio waves.

According to one scientific, this new technology will “create a super-secure communications network, potentially linking people anywhere.” China was reportedly planning to launch 20 of the satellites should the technology prove fully successful.To check China, Washington has been building a new digital defense network of advanced cyberwarfare capabilities and air-space robotics. Between 2010 and 2012, the Pentagon extended drone operations into the exosphere, creating an arena for future warfare unlike anything that has gone before. World War III: Scenario 2030The technology of space and cyberwarfare is so new, so untested, that even the most outlandish scenarios currently concocted by strategic planners may soon be superseded by a reality still hard to conceive.

In a 2015 nuclear war, the Air Force Wargaming Institute used sophisticated computer modeling to “a 2030 scenario where the Air Force’s fleet of B-52supgraded withimproved standoff weapons” patrol the skies ready to strike. Simultaneously, “shiny new intercontinental ballistic missiles” stand by for launch. Then, in a bold tactical gambit, B-1 bombers with “full Integrated Battle Station (IBS) upgrade” slip through enemy defenses for a devastating nuclear strike. That scenario was no doubt useful for Air Force planners, but said little about the actual future of US global power. Similarly, the RAND War with China study only compared military capacities, without assessing the particular strategies either side might use to its advantage.I might not have access to the Wargaming Institute’s computer modeling or RAND’s renowned analytical resources, but I can at least carry their work one step further by imagining a future conflict with an unfavorable outcome for the United States.

As the globe’s still-dominant power, Washington must spread its defenses across all military domains, making its strength, paradoxically, a source of potential weakness.

As the United States enters an election year, prospects for global stability remain uncertain. President Trump’s foreign policy stood at odds with those of his predecessor, and will likely a central point of contestation in the election. At this point, several crises might emerge that would not only turn the election, but potentially bring about a wider global conflict.

Here are the five most likely flashpoints for world war in 2020 (See my World War III lists from back in 2017, 2018 and 2019).

None are particularly likely, but only one needs to catch fire. Let the wars begin!

Iran-Israel:

Iran and Israel are already waging low-intensity war across the Middle East. Iran supports anti-Israel proxies in Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, and elsewhere, while Israel feels comfortable in striking Iranian forces across the region. Israel has taken steps to quietly build a broad anti-Iran coalition at the diplomatic level, while Iran has invested deeply in cultivating ties with militias and other non-state actors.

It is hardly difficult to imagine scenarios that might bring on a wider, more intense war. If Iran determines to re-embark on its nuclear program, or decides to discipline Saudi Arabia more thoroughly, Israel might feel the temptation to engage in broader strikes, or in strikes directly against the Iranian homeland. Such a conflict could easily have wider implications, threatening global oil supplies and potentially tempting the United States or Russia to intervene.

Turkey:

Strains between Turkey and the United States have only grown over the past year. Tensions increased dramatically when the United States unexpectedly gave Turkey a green light to clear Syrian border areas of U.S.-supported Kurds, then immediately issued an about-face and threatened Ankara with sanctions. All the while, an arsenal of US nuclear weapons, by all accounts, remains at Incirlik Air Force base. Certain statements by President Erdogan suggested that he has immense aspirations for Turkey, aspirations which might include nuclear ambitions.

The state of the relationship between the U.S. and Turkey has decayed to the extent that some fear for the future of the NATO alliance. No one expects Erdogan to really go through with an attempted seizure of the weapons, and even if he did it’s unlikely Turkey could break the safeguards on the warheads in any kind of reasonable time. But Erdogan is not known to compartmentalize issues well, and it’s possible that linkages with other problems could push Washington and Ankara to the very edge. And of course, Russia hovers on the edge of the problem,

Kashmir:

Over the past decade, the gap in conventional power between India and Pakistan has only grown, even as Pakistan has tried to heal that gap with nuclear weapons. Despite (or perhaps because) of this, tensions between the rivals remained at a low simmer until steps taken by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to reduce the autonomy of Kashmir and to change citizenship policies within the rest of India. These steps have caused some unrest within India, and have highlighted the long-standing tensions between Delhi and Islamabad.

Further domestic disturbances within India could give Pakistan (or extremist groups within Pakistan) the idea that it has the opportunity, or perhaps even the responsibility, to intervene in some fashion. While this is unlikely to begin with conventional military action, it could consist of terrorist attacks internationally, in Kashmir, or internationally. If this happened, Modi might feel forced to respond in some fashion, leading to a ladder of escalation that could bring the two countries to the brink of a more serious conflict. Given China’s looming position and the growing relationship between Delhi and Washington, this kind of conflict could have remarkably disastrous international ripple effects.

Korean Peninsula:

A year ago, hope remained that negotiations between the United States and North Korea could succeed in permanently reducing tensions of the peninsula. Unfortunately, core problems in the domestic situations of both countries, along with a puzzling strategic conundrum, have prevented any agreement from taking hold. Tensions between the two countries now stand as high as at any time since 2017, and the impending U.S. election could imperil relations further.

The Trump administration continues to seem to hold out hope that a deal with North Korea could improve its electoral prospects in November. But North Korea has no interest in the terms Trump is offering, and has become increasingly emphatic about making its disinterest clear. Recently, North Korea promised a “Christmas present” that many in the United States worried would be a nuclear or ballistic missile test. It turned out to be nothing of the sort, but if North Korea decides to undertake an ICBM or (worse) nuclear test, the Trump administration might feel the need to intervene forcefully. In particular, President Trump has a reputation for pursuing a deeply personalistic foreign policy style, and might feel betrayed by Supreme Leader Kim, producing an even more uncertain situation.

South China Sea:

U.S.-China relations stand at a precarious point. A trade deal between the two countries would seem to alleviate some tensions, but implementation remains in question. Economic difficulties in China have curtailed some of its naval construction program, just as a flattening of the defense budget in the United States has moderated shipbuilding ambitions. At the same time, China has worked assiduously to assure its relations with Russia, while the United States has sparked controversies with both South Korea and Japan, its two closest allies in the region.

Under such circumstances, it seems unlikely that either country would risk conflict. But President Trump has staked much of his Presidency on confrontation with China, and may feel tempted to escalate the situation in the coming year. For his part, President Xi faces the continuous prospect of turmoil at home, both in the Han heartland and in Xinjiang. Both sides, thus, have incentives for diplomatic and economic escalation, which always could lead to military confrontation in areas such as the South or East China Seas.

What Does the Future Hold for 2020?

The prospect of global conflagration in 2020 is low. Everyone awaits the result of the U.S. election, and a better understanding of the direction of US policy for the next four years. Still, every crisis proceeds by its own logic, and any of Pakistan, India, China, Israel, Iran, Turkey, or Russia might feel compelled by events to act. Focus on the election should not obscure the frictions between nations that could provide the spark for the next war.

Dr. Robert Farley, a frequent contributor to TNI, teaches at the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky. He is the author of the Battleship Book and can be found at @drfarls.

Image: Reuters.